Magdala de Nemure:Volume01 Chapter1

Act 1[edit]

There existed a group of people known as Alchemists.

To nearly all, they were of the same nature as demons and witches.

It was nighttime – a time for the inhospitable winter weather to intensify. Any vegetation would seemingly hibernate, with branches waning under the weight of snow, whole limbs stripped of their colorful foliage.

Kusla was dragged from his arms by the knights in metal headpiece out of his cell. He considered his appearance in this abominable state, and felt that the opinions people had of him were not all too ridiculous after all.

The small window guardsmen would use for a view of the outdoors from inside the tower was unsealed. Glistening above the landscape were many stars which seemed so delicate that the buffeting winds outside would sweep them away.

“You couldn’t see the stars from your cell window?”

Looking over his shoulder to speak, the aged knight leading the pack noticed Kusla slowing his pace. In his right hand was a candle holder, while the left rested on his hilt, ready for anything unexpected.

Noticing the ring wore on the knight’s little finger, Kusla could only help but quell his urge to grin.

“I could, but it’s different when thinking the stars symbolize my freedom.”

Raising his eyebrows in unspoken surprise, the knight turned to continue onward. Kusla was again lurched by the guards flanking him, yet he chuckled with another look at the ring on the old knight’s hand.

There was a deep blue sapphire mounted on the ring. It was a gemstone that claimed superstitions of granting wisdom and calm to those who wore it, with the added ability of discerning traps. If pure silver was a metal used to counter evil gods in the form a sword, sapphire served like a holy shield or staff.

He probably wore it so as not to be fooled by Kusla’s words, or to protect himself from something even harder to deduce.

Kusla guessed what the old knight was thinking, humming carelessly as he observed through the window a scintillating night sky.

Even an unwavering grey knight believed superstition in the face of uncertainty.

Shrouded in obscurity, Alchemists were only feared.

They were often said to be people who spent their days shut in dark homes trying to turn lead into gold, formulating medicines to reverse the effects of aging, attaching corpses together to create brand new organisms, and striving for other sorts of futile aim.

Although Kusla could not deny that such people existed, his opinion was that most considered “Alchemists” were not so vain in their work. However, it would not be possible to explain exactly what they did in a few mere sentences.

The term “Alchemist” was simply a provisional name for those in the practice of Alchemy, colloquially used also for people who never know what they are doing.

More than being incomprehensible in their line of work, the place of Alchemists in society was not understood. They were unlike the rulers governing a city, the clergymen raising believers, or the guild masters managing their members; Alchemy did not fit into the recognizable facets of life for other people, thus granting it the perception of triviality – of uselessness.

When a king reigned over his city, it was traditional to divide the economic functions of his subjects into four groups: Nobles, to oversee vast estates of land and facilities; clergymen, to counterbalance noble authority; merchants, supporting markets, and; craftsmen, who contributed to architecture and the inflow of wealth to their city. Given this division of people into four ascribed categories, the management of a king’s subjects was categorically simplified.

To actuate his hand, the king would entrust the leaders of each organization with appointment officially recognizing their status. Established craftsmen would operate as guild masters over their membership. Bakeries, Butchers, Blacksmiths, and virtually every other necessary economic activity had a Guild.

The knights dragging Kusla through the snow were no exception from this system.

Their clothing, armor, candlesticks, pay, even the authority to bring Kusla out from prison – it was managed by royalty.

However, this management network was not developed to embolden royal frivolities. There was a need for centralized maintenance of a large city, and this management network was the result.

The laws of a city were established by a council comprised primarily of the famous people and nobles living within. This council established a code for a city’s residents regarding what could or could not be done under the law.

Without that, a large city probably would not be capable of existing for one month.

Most notably among the reasons for disorder to ensue were the notoriously territorial craftsmen, who would undoubtedly trigger bloodshed.

Thus, all the guilds would regulate their members’ actions, and the degree to which they performed such actions, so as to try mitigating strife as much as possible.

For example, those Blacksmiths in charge of forging swords would only forge swords, while knife craftsmen would only make knives; there was strict classification between swords and knives. If there were any ambiguities in the difference, those who spent their lives forging swords would be inspired to make knives, and may end up robbing the knife-makers of potential customers. A source of conflict would be created as bakers start to operate as butchers, or butchers selling meat outside other shops in the middle of the night to harm the business of motels and inns. Perpetually, only chaos and decadence would exist in society.

God seemed unwilling to reign with Divine Punishment in this world, so knowing how to avoid conflicts altogether rather than settling them personally became an indispensable asset in life.

Using the Blacksmith Guild as an example, the subdivisions of labor within all four categories were made to a nauseatingly complicated extent.

There were various occupations for the Blacksmith, like that of the swordsmith, whetting blacksmith, and farrier; locksmiths, plumbing pipes builders, incense makers, special metals craftsmen, and other specialists’ work could also be ascribed to Blacksmiths.

Every discernable craft seemed to have its own classification as a subdivision. Aside from sharing the same category, these subdivisions were mutually exclusive to one another. If a tradesperson wished to expand the scope of their wares, they were required to purchase the privileges for marketing each desired craft.

This was the venerated order those of society’s upper echelon maintained.

Still no exception to this system, Kusla was a man who allegedly tried transforming lead into gold.

Among the many subdivisions of four categories, how would his work be classified?

Was he a lead pipe manufacturer? A goldsmith? Or perhaps he should be associated with those metallurgical workers who created gold by smelting ore obtained from mines?

Though some title of ‘lead-to-gold transformer’ could be applicable, what would be researching the act make him? If such researchers truly existed, how would they be classified? Additionally, if turning lead to gold was against the proper conduct of mortals established by the ecclesiastical God, then wouldn’t classification be under The Church’s discretion rather than royalty?

Just one case of turning lead to gold was already so convoluted. Yet there were still more possibilities: What of transforming lead to silver? Turning silver into gold? Lumping corpses together to form a new creature? Creating a de-aging medicine? What about the other things not immediately identifiable but bound to occur in the future?

Considering this, it might not be the end-all for a city’s existence, but such a mess of order would be virtually catastrophic to any orderly society.

In truth, the scheme was already plaguing society, as this problematic example Kusla spun was not entirely made up; for reasons not unrelated to producing gold, there were quite a few dignitaries in the city already willing to invest money in Alchemists.

There were those who delegated such research for their eternal life to remain secured through The Church, mostly for the riches. A minority of those who sought research of transforming metals alchemically did so for knowledge. Research of this kind might lead to developments for increasing the efficiency of ore extraction, or improvements in metal purity after ore smelting. Given such an upper-hand, the wealth of an individual or even the wealth of an entire nation could compound sharply.

When it came to increasing the efficiency of extracting ores, for example, it would also require very disparate elements working together – like the strength of the ropes used to deliver the rocks, the durability of excavating tools, the design of such excavating tools, the invention of corrosives used to dissolve rocks, and further steps in the line of production. The industry of craftsmen, in its insular culture of many distinct subdivisions, would destroy itself before arranging the supply chain fit for this one unique task. Even if they could find a way, the craftsmen needed to be wary of exceeding their sub-divisional boundaries, with each transaction they would make in the city government’s plain sight.

Thus, unlike craftsmen, those who merely sought “methods” instead of creating things were prized – but there was no management, organization, or standards used to govern them.

Moreover, when something new and foreign occurred, the issue of religion was certain to be implicated.

Even a lady, sensitive to trends, would be interrogated as a heretic if she were to break regulations on appropriate hairstyle. As a result, people were appropriately afraid of deviating from what was considered acceptable.

The Church did not take kindly to heretics, so arousing the suspicions of fellow neighbors was less than desirable for anyone.

Craftsman implicitly understood not to attract unwanted attention, just as all others subject to this system.

Those in authority who wanted to fool other kings and rulers had to do the funding themselves, raise the appropriate people, and protect them under their power. This was common practice in the world, especially in the case of those researching metals, from whom rulers hoped to attain unrealistic results. Over time, Alchemists earned their unsavory name, yet the expectations many had in Alchemy continued stirring.

It was not out of compassion that Kusla was uncaged by this armored trio.

They brought him as a member of the Knights of Cladius – a large organization with an almost unwieldy authority more involved in the business of hiring Alchemists than any other.

“I suppose you don’t mind listening to me as you eat?”

Marinated pork, bread baked with cheese, and warm mead were soon prepared. Kusla, who was only able to eat cold onions and black bread in prison, devoured the meal heartily. The warm mead trickled into his bellow, and he felt his stomach was finally taking form again.

“I never thought it would take two weeks… but we’ve formally obtained jurisdiction over you.”

“So I still have that much value, huh?”

Kusla held a bun in the palm of his hand, peeling away its crispy outer layer. He removed a small bottle from his pocket, sprinkling its contents over the bread’s doughy insides.

“Hey, that’s–”

“It’s just salt. Salt.”

The old knight was nearly pale with shock.

“What, so you were joking…?”

“Nope, here’s the arsenic.”

Kusla proceeded to remove another bottle from his pants pocket, the old knight’s eyes agape.

“I can give it to you if you want.”

“…It’s probably just salt anyway.”

“It’s better for both of us if that’s what you believe.”

Kusla returned the bottle to his pocket, the old knight feigning indifference as he leaned on the back of the chair. He then rubbed his eyes, staring at Kusla, yet leaning back ever so slightly more.

“Why must you make yourself out to be a scoundrel? You have common sense and decision-making abilities – rare traits that separate you from the rest. Don’t laugh. I really feel this way. You are also virtuous, and have many other things those others lack. So why? Why did you steal the bones of a saint from The Church vault for your Alchemy? Are you insane? Did you want to die?”

“There was no other way to test it out.”

“You’re lying! I’ve read the reports of your experiments. You of all people would challenge such superstitious methods!”

Kusla’s mouth was stuffed with bread, his back arched inly so far that his chin nearly rested on the table. He lifted his gaze to the instigative Cladius Knight.

Their silence was covered by the darkness of night. The knight continued, hesitating to choose his words this time.

“Good thing it was before the fire was lit. If the skeleton was burnt, you would be turned to ash. Then…”

He was almost lethargic.

“…Why? Why must you waste such talent?”

“Why?”

Kusla’s mouth was again stuffed with bread, and he tilted his head in response.

He shrugged, swallowing the mouthful like a bird, following through with mead.

“I don’t really understand myself, but maybe you can understand if you slice open the skull of a highly-skilled Alchemist.”

“…Hm.”

The old knight sighed at Kusla, who relentlessly indulged in the bread.

“Is it because of what happened to Friche?”

A pause. An irrevocable pause.

“As expected… but Friche was–”

“I don’t know. She was a spy for the Pope’s faction, and wanted to steal my metallurgical techniques, right?”

“…Yeah. There’s solid evidence. Lots of it.”

“Then wouldn’t it be better to kill her as I enjoy myself with alcohol? Cut away her shapely collarbone which vibrantly defined itself every time she laughed, slice off those thin and exceptionally prominent ribs, gouge out that healthy liver of hers which will throb so beautifully upon even the gentlest touch, carefully rummage through her intestines to look for something; I can do anything to get what I want, even if it’s something hidden inside the stomach… I’m not lying.”

Kusla gulped down the lukewarm mead.

He was drinking mead just the same back then.

The irony of it all was almost overwhelming.

Kusla gave a hideous stare to the knight.

“Because I really wanted to try using the bones of a saint to smelt iron for a very long time.”

Those of The Church would have fainted from fear, but the old knight remained characteristically unmoved.

“What happened to Friche… I can’t help in that, and I really feel pity over it. But you were the one who leaked the news about what you wanted to do… because you loved her, I suppose?”

The aged knight’s specialty was investigation of new members, after all.

At this point, Kusla almost felt it wasn’t worth the effort to answer.

“If not for the fact that your plans were divulged, you two definitely would have been killed together.”

Kusla let out a nonchalant sigh.

“Do you want to resign as an Alchemist?”

It was a fatherly question.

Alchemists faced endless scorn for straying away from the right path, detested as heretics, and even as they could find protection from those in authority, they were only seen for their talents and lives. Occasionally, they met people with whom they got along with well, but all too often such people were spies.

Do I want to abandon this lifestyle so full of adversity?

“I can recommend you. It’s not easy breaking away from us Cladius Knights… but I can find you some decent jobs. It’s a good thing our organization’s huge.”

Kusla eyed the bearded man before him – his green eyes shone a light of compassion. Such a good man, he thought. This fortunate individual was born from a prestigious background, living his proud life as a knight to this age.

His words were most likely not lies; especially because the two had known one another for such a long time.

Kusla pressed his elbows on the table to support his head, his motions exaggerated in a way similar to someone trying to overcome drunkenness after too much alcohol.

Even in his impairment, Kusla resolved not to allow himself to falter now of all times. He fought the weight on his eyelids to keep an attentive gaze as he answered the knight’s offer.

“I’ll continue on. I have no other choice.”

Despite consistently finding himself in circumstances such as these.

The old knight turned away from Kusla, heaving a heavy sigh – ostensibly in pity for so unfortunate a person.

“No matter what kind of experiences you go through, your curiosity will never cease. It’s like you people caught a disease. It’s for an extremely stupid reason, at that.”

“Magdala, you mean?”

The old knight cleared his throat dryly, and he was probably unwilling to express his thoughts about this concept directly.

Alchemists were an existence woven deep in the fabric of the world’s social order. They were not a part of any formal system, and their identities were never clear. They were often frowned upon and held in contempt. However, there were desirable aspects of being an Alchemist, and many Alchemists were talented artisans, but there was good reason to lead the scornful life of an Alchemist.

To any observer, it was an extremely foolish aim, their dream – perhaps this was what set their insatiable curiosity loose.

And so, the afterworld to which Alchemists looked forward was christened as the land of Magdala.

In retrospect, Alchemists simply sought to enter Magdala, gambling everything on it – including their lives and pride.

“Because of you, the metal productivity here has increased tremendously, and the fuel cost has lowered quite a bit. The amount of money you helped the knights save was enough to rescue you from the Pope’s faction planning to burn you at the stake.”

The old knight paused to survey Kusla’s reaction; he was staring at the table, motionless.

“The higher-ups considered it a waste to squelch that talent.”

“Where’s the next workshop?”

He asked, showing no interest in the old knight’s words.

An Alchemist’s occupation was a unique one, and it required many diverse craftsman-like skills.

There were few replacements, and death was common.

They were often killed by others, and accidents were frequent.

Alchemists were like moths of gold flying dangerously close about a fire.

“It’s just that I’ve never seen such a vile act. Even the Knights can’t release you scot-free.”

“…I’m already prepared.”

“Gulbetty.”

“Eh?”

Kusla unwittingly lifted his head; the placename took him aback.

“Near the front lines? Is it really alright to go somewhere like that?”

“I think it’s the perfect case for you people.”

“Gulbetty… Gulbetty…”

Kusla mouthed the word over, and after a while, came to understand what the old knight meant.

“Us?”

“I suppose you know Wayland?”

The old knight’s expression was bitter.

Were it not for that, Kusla would probably have feigned ignorance to his question; the name did surprise him, after all.

“Are you serious?”

“Dead serious. You and Wayland are to go to the workshop in Gulbetty.”

“Heh.”

He did not scoff at this, or even show his displeasure, but his astonishment compelled him to cough.

“What are you thinking!? You mean that Wayland!? The man who poisoned some Monastery Archimandrite to death and was arrested!?”

“Saint Ariel Women Monastery, the elegant Monastery full of noble princesses.”

“Heh?”

This time, Kusla clearly smirked and shrugged his shoulders.

“Then why did The Church leave them?”

“Who knows? You two are Alchemists, aren’t you?”

The ones who make the impossible possible.

Turning lead into gold was a trademark phrase of theirs.

“In other words, Wayland and I are going to be in the same workshop?”

“You two were in the same workshop during your apprenticeship, so I suppose you two are amicable.”

“You must be joking. He poisoned my food seven times.”

“I heard you poisoned him nine times. Was it not because of your experiences with him that you two were able to escape being assassinated by poison?”

“Well, I think we’ve probably got Taurus’ divine protection.”

The sapphire which granted the intelligence to discern traps was a symbol of the Zodiac Taurus. Of course, he was mocking the old knight for wearing a sapphire ring, and the old knight consciously withdrew his left little finger.

But it had been a while since last Kusla heard the name Wayland, and he felt the hair on the back of his neck rise.

“What’s your name? I don’t think I’ll be so easily pardoned. There has to be a serious punishment for my crime.”

“I didn’t hear the specifics, but I did dredge up a few rumors. I will be in trouble if I say it out here. The order I received from above was to deport you, and that you must obey sincerely. If you do well, your debt to the Knights as an Alchemist will be written off, but if you fail, the debt remains. Of course, the premise is that,”

The old knight said with a sigh.

“That you’re to turn lead into gold. Everything’s set.”

“I’ll do it then.”

Kusla answered immediately. Although there was no room to decline, he accepted the task heartily.

“It’s just that I’m a little curious about what the higher ups are thinking.”

The old knight accepted Kusla’s curiosity with an unchanging expression; not even the faintest smile crossed his lips.

“I don’t understand either.”

“…”

“I miss my days on the battlefield. Back then, you could see the horizon at a moment’s glance, no matter where you were.”

These words, spoken with a sigh, did not sound at all to be a joke.

The Cladius Knights.

They were known by all across the land; they held unparalleled authority. It was an organization of great wealth and military strength.

In the past, The Church organized an army to launch a crusade and reclaim the holy land which laid in the East. This was the birth of the Knights.

The promised land recorded in the scriptures, Kuldaros, had long been occupied and trampled upon by pagans.

The Pope, Franjeans IV, could not accept this and took action against the pagans, making use of the theological theory presented by the distinguished theologian – Amelia’s Saint Jubel. He dubbed the act of reclaiming the land a crusade; this signified that, even if they were to invade, they would receive God’s forgiveness.

Twenty-two years had passed since the crusade began, and it had not yet come to an end.

Countless men wore armor engraved with the emblem of The Church, and some even engraved the emblem upon their own skin with ink – these men traveled to the East, their weapons in hand. Swordsmen and staff-wielding believers on pilgrimages alike wished to be buried in the promised land recorded in the holy scriptures.

The Cladius Knights’ former identity, the Cladius Brotherhood, was an organization which provided services similar to a hospital’s – namely housing and medical treatment – for those traveling to the holy land, be they a soldier who was soon to step on the battlefield, or believers on a pilgrimage.

However, there were quite a few people who died of wounds or disease before reaching the holy land.

They left wills leaving all of their inheritance to the Cladius Brotherhood, and departed from this world.

The Cladius Brotherhood obtained this fortune, and their wealth accumulated. It was necessary for them to strengthen their independent fighting force to maintain their fortune, but in the end, the gentle monks became greedy knights. They could not be satisfied with the final requests of pious believers, and in their greed, became an organization with a voracious appetite for wealth.

At this point, their wealth and the number of their followers had exceeded the head of The Church, the Pope’s own faction. There was not a man on Earth with the power to rival the Cladius Knights who held such overwhelming military might.

Although the rumors surrounding Kusla were exaggerated, he had been sentenced to death by The Church four times, and had managed to narrowly escape each time. This was proof that, for as long as the Knights, who were adept at measuring outcome against cost, felt that Kusla was still of value, even The Church would have difficulty sentencing him to death at the stake.

The same held true for Kusla. If there was profit in it, he could accept selling his life to the Knights as an Alchemist. This was because Kusla wished to, at any cost, reach The Land of Magdala.

To this end, he had no choice other than to take the path of an Alchemist and focus on research. The research, however, required a vast sum of money, and abundance of materials, a great deal of time, and the authority with which to protect himself from danger. If he were to lose the protection of the Knights, it would become impossible.

Thus, Kusla was supposed to work for the Knights like an obedient sheep. His act of throwing the bones of a saint into the furnace in order to see the results of the smelting was essentially suicide; it would not be odd for him to be abandoned.

After his release from prison, he departed for the northern town of Gulbetty during the freezing winter. He recalled the conversation he had with the old knight in the carriage, Friche’s death, and that old knight’s face.

“Heh.”

Kusla gave a wry laugh.

Unfortunately for him, he failed.

Kusla had thought there was a possibility of it working. Even after dumping the saint’s bones into the furnace in an attempt to refine metal of a higher quality, he could have been saved, but he panicked because Friche was killed. As he was overly sad, he did not know what he was doing. These reasons, coupled with what he had already accomplished at this point, could have protected him from the death penalty.

Were this not true, he could not have chosen such a treacherous path.

“…I really missed out on a golden opportunity.”

Kusla muttered with a faint sigh.

It was entirely true that, when refining metal, burning bones could alter the outcome. At times, ash could be used in place of bones.

Yet the old knight’s words were more or less correct. Friche was a good girl, and even after he had vaguely realized she may have been a spy, he might have been mesmerized by her innocent smile. It had been a while since he last met someone with whom he was happy to be together with.

Even so, when asked about the extent of his melancholy, Kusla hadn’t any confidence with which to answer the question.

Alchemists originally believed in vicissitudes – that everything on this Earth was ever-changing. People died, the state of nature was always unique, and the old became anew in all things – and because of this, he believed that lead could become gold, and that foolhardy dreams could turn into realities.

But change waits for no man.

He continued to believe in and pursue change as he refined his metal; this was the essence of Alchemy.

And so, the journey finally came to an end. Kusla’s haunches had become stiff from sitting, and the carriage finally stopped. The driver, who had been silent for the entire trek, finally spoke.

“We’re here.”

“…”

Kusla stepped outside of the carriage, and the first thing he did was stretch.

For ten days he had been inside that carriage to avoid being sighted by passerby.

There were plenty of books he had to read along the way, so boredom was kept at bay despite his bodily aches. He felt as though it would be fine if they were to continue traveling.

It was a cold but clear day outside. The clarity of the air was unique to wintertime as he knew it.

The morning market seemed to have died down, and the farmers, who were probably from the surrounding villages, leisurely lead their cattle home for the day. All was seemingly still to Kusla, and in the ordinary lives of these town-goers, the only change came with the change of seasons; they would have a family to come home to each day.

The girl who had expressed such interest in him in the past was, inevitably, a spy. He realized he had fallen for her, but she had already been slain the moment he turned away from her.

Kusla did not think of this as something worth pity or sorrow. He considered the possibility of having much more regressed emotions than others thinking about it. Though Friche’s fate was pitiful, and for her to be revived would be best, Kusla remained sane even after witnessing her death. All he was left with now was questioning as to how her death could be used for his Alchemy.

Kusla wondered if this was why he felt a pang in his chest thinking of her. There was no long-lasting sorrow, and he wasn’t burdened with anxiety. His apparent distance of emotions pained him perhaps even more than Friche’s own death.

This is quite an excessive wish. Kusla sighed as he left the city’s checkpoint. His identity was only confirmed by a single guard, and his bags remained untouched; such were just a few of the special privileges of the Knights had. Most of the council members in this small town were forcefully taken under the jurisdiction of the Knights, and to this upstart town’s citizenry, it was far from amusing.

It for this reason that they normally looked upon the Knights with disapproval, but the real reason Kusla got through so remarkably unscathed was due to his status as an Alchemist too. The people of this town with common sense would rather conspire with heretics than involve themselves with an Alchemist.

Kusla’s back ached from the ten days he spent riding in a carriage; he walked with methodical care to avoid worsening his injuries.

The city’s walls were thick, and near the gates there were numerous facilities offering hospitality to the guards. The guards patrolled through some vestibule, presumably inside of the city’s walls, with bows and catapults in stacks. Their armor was not covered in paint, but in oil – or perhaps blood that had yet to dry completely.

Alchemists were only summoned for matters of the utmost urgency.

Most notably among the reasons for summoning his ilk: Issues concerning money.

Were it simply a case of monetary issues, the solution would be quite simple and direct – like chopping someone’s head off with a sharp axe.

Kusla whistled glibly as he entered through the gates, put at ease by the town’s picturesque scenery behind those fat walls. In terms of scale, Gulbetty was of another caliber than what Kusla was accustomed to.

There was ample river water flowing through the portway, and four arched bridges stretching across it.

After passing the gates, what he found was there precisely as had been described to him. The freight carriages and mule carts were gathered in a group to the side of the road. Wagons laden with chicken cages passed him.

Some hooded foot travelers, their eyes tanned, each carried a cargo larger than themselves. They were, most likely, part of a trading company that passed through the snow-capped mountains at the end of the year, and the cargo they carried likely consisted of pelts obtained from hunting or other items like amber and beeswax. The seasonal journey they made to turn a profit was known to be arduous.

The road was covered with the dung of horses and mules. A hoard of domesticated pigs and escaped chickens emerged from the throngs to the side of the road, trotting about insouciantly.

Of course, not everything was so trivial: There were treacherous people who leaned against the wall, observing the townspeople; robbers, bandits, prostitutes, and even hunters who were present trying to, on behalf of their respective leaders, find a chance to bag the escaped farm animals. Preoccupied with fondling their coin, the only dangerous wallflowers not interested in the loose livestock were the money exchangers of the black market – and in a sense, theirs was a form bred from luck and chance. The reason these black-market dealers could be in daylight was because they were necessary to so many people.

Kusla was not the type to relish such calm.

If he could choose, he would be in a more noisy and bustling atmosphere the interior gates.

Also, there was a port in this city; that’s where its heart should be.

Seeing as the area around the gate was boisterous, there should be even greater a clamor near the port.

The Cladius Knights had absolute control over the town.

So long as he wore their crest, no man would dare to wrong him.

“Not bad.”

Kusla took a deep breath, perhaps in an attempt to cleanse his lungs, inhaled the dust-filled air, and smiled.

The youths inviting customers into their shops, the prostitutes, and the black-market dealers dared not approach Kusla, as an unusual air was about him they saw best to avoid.

“Where to?”

The driver asked Kusla, but did not look to his face.

“Who knows? I heard someone’s here to meet us.”

The driver held his silence. His left finger, which held the reins, was halved, and there was a large scar from a blade across the side of his face, which he concealed fairly well with a hat and beard extending behind his ears; he was likely a retired veteran who had long served the Knights. It was probable that he was chosen to kill Kusla, should he try escaping, rather than guard him.

“…”

The driver suddenly lifted his head.

He sensed the gazes upon them in an instant, like a wild hare.

He snapped the reins and turned the carriage toward a corner of the intersection.

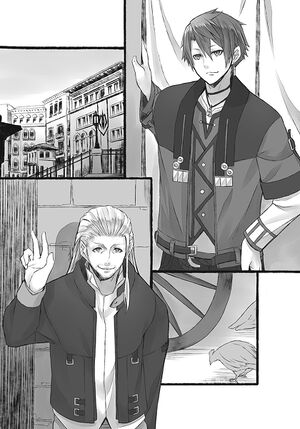

A scrawny man stood there, a grin on his face.

“You’re safe, hmmn?”

He placed particular emphasis on the vowels at the end of the question. His ruffled blond hair was tied back in a bundle, and one had to wonder whether he wished to trim his unkempt beard or leave it as it was. Even so, he was the only man in the world who would welcome Kusla with a grin.

Kusla reflexively curled his lips, returning the smile, and spoke.

“You’re one to talk. Why are you still alive?”

“I guess God was protecting me!”

Again, he spoke with that peculiar quality of drawn vowels for emphasis, and it was all too familiar to Kusla. Be it on purpose or not, poisoning an Archimandrite to death would certainly result in punishment with the death sentence, and yet there stood Wayland before him, very much alive. Alchemists were, just as that old knight had said, magicians.

“And how did you survive? I heard you dumped the bones of a saint into a furnace and burned them?”

“The fire wasn’t lit, and the key was that I gave an excuse. Divine Retribution spared me, for I was innocent and thought the saint was cold.”

Wayland kept walking, looked at his fingernails, and shrugged.

“What about you?”

“Me? I didn’t poison him.”

“…What do you mean?”

“In other words, while that fat man was guzzling down his food, I appeared in front of his table, smiled in front of him, and shook a little bottle in front of him. He then turned pale and dropped dead.”

This was the trick Kusla had alluded to when he was teasing the guards, but such methods were very real.

Because the tactic killed a man, however, it seemed Wayland had planned it well in advance.

“But why would you do that?”

“He was hitting on my girls.”

Wayland’s expression seemed to ask, “What other reason could there be?” To which Kusla had no choice but to nod in acceptance.

“Wasn’t he a Monastery Archimandrite?”

“I said he was flirting around with the nuns. The Archimandrite of a female monastery need not be female.”

Kusla could only shrug at Wayland’s ability to manage such an amazing feat. Even with the decadence of clergymen, Wayland romantically involved himself with the nuns, who might as well have been caged birds.

“That fatty did a lot of bad things people don’t normally see, and, in the people’s eyes, I was getting rid of a plague. The nuns of the monastery were begging for me to save them, so I got off scot-free. I’m worshipped as a hero at the monastery.”

“You’ve always been good at this type of thing.”

“It’s just that you’re not good at it, Kusla.”

Kusla had once fallen for a spy’s sweet words; he fell in love, hook, line, and sinker, only for her to be killed. He shrugged and kicked aside a chicken as it flew by.

“But it’s really shocking…”

Kusla sauntered forward and listened calmly.

“I never thought I would be working in the same workshop as you again, Kusla.”

“That’s my line.”

“How many times have we met in the Knights’ prison?”

Kusla had been in and out several times, and Wayland himself was no slouch in this department, so the two of them would frequently meet behind bars.

“But when was the last time we were together in the workshop?”

Wayland paused to answer.

“Hm… that was five years ago, right? I really miss those days.”

Whenever they recalled what happened five years ago, they felt they had been nothing but immature fools – a thought one could only grimace upon.

The two of them were constantly quarrelling, and, after learning a little, would steal poison from the workshop for use in the other’s food.

However, their master was a devil far worse than they, so on the day of their graduation, Kusla and Wayland planned to poison him. After their master had finished half of his mercury-laced food, they were apprehended.

When the two of them parted ways, Kusla bid Wayland farewell, and they both exchanged genuine smiles. The scene was still fresh in Kusla’s mind.

“You were easily moved to tears back then, Kusla.”

“You’re one to talk. Aren’t you pretty well acquainted to teariness?”

Wayland shrugged, abruptly stretched his shoulders with audible relief, and turned back to face Kusla.

“Anyway, let’s hurry to greet the one who’ll be hanging us, and head to the workshop. I’m looking forward to it.”

The executioner he referred to was the one in charge of alchemical operations with the Knights who owned a workshop in the city.

He would be involved in not only providing the Alchemists’ necessary resources for work, but also in assisting the Alchemists, were they to be etched with a certain brand from some Church faction or sentenced to be burned at the stake. On the other hand, if an Alchemist could no longer serve the Knights, or was deemed worthless, they would normally either sell the Alchemist to The Church or assassinate them.

As unusual as it seemed, the Knights truly did reserve the right to kill on their own whims.

That was why these individuals were called ‘Hangmen’.

They were not known as executioners because an Alchemist didn’t have the right to accept a swift punishment like decapitation, which was used on the common folk. Burning at the stake killed too quickly, so it could be considered too easy as well. Basically, they would hang an Alchemist with the dogs, and the Alchemist would be scratched and gnawed upon by these agitated dogs for three or four days before they could die.

Kusla had to remind himself not to smirk internally as he questioned Wayland.

“So, you haven’t been to the workshop yet?”

“Nope. I just sent the goods there. I only arrived this morning with the Knights’ Freight Unit.”

“So you’ve just arrived?”

“Right.”

“Couldn’t you have gone first?”

“How could you expect that of me?”

Wayland dragged his voice out mockingly.

“Part-ner~?

“I’m shivering.”

“You’re cruel~!”

Wayland enjoyed imitating a dog’s whimper, just as Kusla enjoyed teasing the prison guards. The town of Gulbetty was located near the frontlines, and the citizens, who were accustomed to seeing both mercenaries and knights no differently from thieves, would panic and hurry away from them.

Alchemists.

Those despicables who strayed from the path.

When he was young, Kusla would reply to spiteful remarks with a cold sneer.

However, he lacked motivation anymore, and, at most, teased the guards. Wayland, on the other hand, seemed no different from his days as an apprentice, and would commit murder without so much as blinking.

“But I agree with going to the workshop. I wish to melt this cold air within me – like smelted metal,” Kusla mused.

“Given its exterior, I think it’s in rather good condition. As expected of a facility on the frontlines.”

This Northern land was where the Cladius Knights concentrated both its finances and military might; they made use of Gulbetty as a base. It was only natural that the northernmost land belonged to the Knights – and there was no one who dared to mock the Knights, as their power was well understood.

Many avaricious Alchemists wished for and dreamt of a workshop situated near the frontlines; with such a position, they could strike while the iron was hot. People would do anything for the sake of winning.

There was an infinite supply of funds, they could have books given to them with priority, and they had the coveted right to do business with the local craftsmen and mines. There were also many benefits for them, like being able to leaf through secret and forbidden books.

Kusla would probably be delighted were it not for the condition by which he had arrived to the front lines: He had to be with Wayland.

“But what about the man who made use of the Gubletty workshop before us? He’s truly a fool to hand over such a nice workshop to us.”

Kusla stepped around a pile of horse dung while speaking, and Wayland replied in a manner not unlike how one might describe yesterday’s weather (in his characteristically drawn voice).

“I heard he died.”

“Oh? Did he die of an accident?”

The two passed a dog leashed to a door, its mouth stained with fresh, red blood. It was likely that it had gone hunting early that morning – the prey was, naturally, some living thing roaming about town.

“No, I heard he was killed by someone in town.”

Kusla evaded the horse dung which lined the roads, offering no response.

Although he understood such things were common, something still concerned him.

The Knights were the ones to assign them this time; clearly, they considered it some form of punishment.

“Don’t tell me we’re working as a pair because of this.”

“Hm… that’s what I think. They’re sending we unscrupulous folks to such a good place, there’s certainly something they’re hiding.”

Wayland scratched his head as he walked, feigning concern.

He was the type to scoop up rocks from the roadside, then cut, grind, and observe and play with them to entertain himself. If he were to look disinterested, it meant he was displeased.

“We might be killed if we’re alone, so two people will make it comforting, huh?”

The two of them walked in silence. Kusla turned to Wayland, and Wayland kicked a pebble.

“Belittled Alchemists are doomed.”

“Haha. That waste of a master taught us that!”

The two of them stood before the hangman’s house.

Kusla recalled that scene from five years ago, and his shoulders stiffened.

“You scared?”

“That’s my line.”

It had been five years since Kusla had bickered with someone in this way.

He wanted to suppress the nostalgia, but was unable to, his mouth curled at the ends.

The pedestrians nearby were terrified, so they parted, leaving a path for the two.

“I know you two specialize in poisoning and assassinations.”

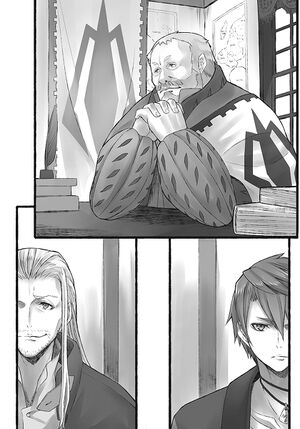

The man held down the parchment with a paperweight made of pure gold, and proceeded to roll his pen fluidly on the table as he spoke.

His elegant handwriting was a treat to the eyes. It was a mystery as to how such a thick, pudgy hand could write so fluidly.

He was the Gulbetty Freight Corps Leader belonging to the Cladius Knights, Alan Post.

It was the Corps’ job to provide food and wine to the soldiers, or to transport certain necessities. It was also the case that most of the Freight Corps were very active on the battlefield.

However, the higher ups among the Knights differed in role.

The Knights promote themselves boldly, claiming their actions are sanctified by Divine Will, and they would use this excuse to collude together with the guilds for trading. The marketplace was essentially hostage to what they do, namely with finances and information brokering, and the same was true for making a profit. That was because merchants naturally sought profits where they do business, especially places in which war was prevalent, and the Knights saw benefit in being the instigators of war.

Alan Post, who sat in front of them, had absolute control over the bloodstream known as finance flowing around Gulbetty. He made lots of profit with his manipulation, and his plump body was similarly enriched as his coffers were. His belly pressed against the hollowed office table as he continued his work.

“Why would I assassinate? My love suffered the same fate.”

“There’s no way I would poison someone! I won’t use poison.”

Kusla and Wayland still in the middle of the room, answering their own questions as their eyes wandered.

“Well, I’m not trying to blame you – just to give my opinion.”

Neither of the two knew quite how to express their delight properly.

Wayland responded by stretching his back, while Kusla started to pick at his fingernails.

“Such actions aren’t bad, however. When you enter a room for the first time, you can only give someone else a first impression once. If you look down on your superiors right at the beginning, it’ll come back to haunt you.”

Kusla darted his glance aside to Wayland, and Wayland did the same to Kusla.

Both of them sighed and adjusted their postures erect as they eyed ahead.

“And when you sense that your secrets are revealed, you pretend to obey, huh? Well, you passed.”

Post handed the parchment to the butler waiting beside him, continued to blink his small and fiery eyes, and went on to rub them.

“Shower the opponent in flowers to make them careless, and then remove their footing. That’s good.”

“You want to show that you’re not an easy superior to deal with, and stop us from spouting anything?”

Kusla spoke as he looked up at the ceiling, and Post’s rotund build quaked in laughter.

“You certainly are smart. These are indeed the two I requested from the Knights.”

Kusla felt something that didn’t fit in what he said.

“…What do you mean?”

“I have to protect my own body.”

“With poison and assassination?”

Post smirked, but his eyes were bereft of any benevolence they had before.

“The best defense is a good offense. This is the only rule I taught myself in the military.”

This time, Kusla honestly looked for Wayland’s expression, instead of it being a mere act.

Looks like we got ourselves into a troublesome situation.

“Your predecessor’s a man named Thomas Blanket. He was an outstanding man, probably reaching his forties, but who is now dead.”

His manner of speech was so blunt and pensive that it was somehow indicative of how one might speak to a wilted flower with dignity. Kusla spoke up.

“Your Excellency Post, was he murdered under your nose or something?”

The leader of this town – to be in such a state. Kusla’s curled lip betrayed the thoughts running through his head.

Of course, if he were someone too easily agitated by such taunting, he would not be sitting in this seat.

“To be honest, that is the case, and we still have not caught the culprit.”

“Not caught?”

“Surprising, isn’t it? The people of The Church, who want to win back authority over this town, are trying their best, but still can’t find out. The death of an Alchemist is normally attributed to some conflict of faith. As long as they can get proof of heretics, they can immediately seize the chance to pull me down.”

The Knights honor God, and not the Pope, who governed The Church.

Hence the explicit need for an independent army, finances, and doctrine all at once.

No matter which town it was, there would be a conflict over the jurisdiction between The Church and the Knights.

“So I say, we have no idea of the kind of people who killed Thomas, and we don’t know why. We don’t know if it was an accident, a slug fest between drunkards, a robbery, or a test of a new sword. Maybe some sort of witch hunt with a bias against Alchemists, or maybe The Church wanted to get Thomas’ Alchemy results and was refused by him. Maybe he defected and was killed to shut up.”

He paused before continuing.

“Well, we don’t know the enemy, and we can’t establish a plan, but we can’t seal the town up like this either.”

“There’s still a method of protection for people like us known as imprisonment.”

“That’s for people who’re higher-ranked than me. Besides, I hate those who slack around and breathe in the same stale air for all their lives.”

Kusla shrugged, raising his hand to acknowledge that he should not have interrupted.

“Right now, the metal equipment in the town is in a most dire state. The war north of Gulbetty is still alright, but most of the mining hills in the north are still in the pagans’ hands. Even if we tried to manufacture and refine weapons in the south, the labor cost would be too high, and there would be too much tax taken along the journey. Also, there are things we have to transport like wheat, rye, barley, grape wine, alum…even the oat those Knights’ military horses consume. If we don’t supply them, there’ll be short supply.”

“In other words…”

People dwelled upon their limited past experiences through life, and may lose foothold over their lives forever. It often took people some time before they realized the time they’d wasted – and some never do.

However, an Alchemist’s life too short to encourage idleness.

Post paused for a moment after being interrupted by Kusla, and seemed to take some delight in picking up from his interjection as Kusla pondered.

“In other words, this town needs Alchemists with exceptional skill in metallurgy to increase the production of metals, but since we’re unable to explain the death of the last guy, we can’t find acceptable successors.”

“In other words, we’re the sacrificial pawns.”

“Even on the battlefield, such people are unnecessary for the sake of an ultimate victory.”

Alright, so we’re sent to our deaths.

Post showed the composure only a man who had given so many other such commands could give. His face was a chilling calm.

Neither Kusla nor Wayland had any intentions of protest.

However, it wasn’t because they lacked the upper hand. More appropriately, an Alchemist wouldn’t care after being this deeply ensnared.

“So you mean we can stay here as long as we don’t die?”

“You said it. Besides, warriors who come back from the brink of peril will certainly become heroes. I don’t think the collateral will be very negligible.”

The workshops near the battlefield have what could be considered an unlimited budget. Normally, it was not a place they would send young and barbaric Alchemists like Kusla and company to operate.

If they stuck with the plan, the risk involved would also be on their shoulders.

“The good thing is that the town is under my control. I certainly won’t allow such violence to happen again, and I’ll clean up this area as much as I can. Do your best.”

Post narrowed his eyes. His expression was grave, the expression of a person in authority, where everyone other than him were mere pawns to be used.

Kusla did not like it, but the reasons guiding Post’s actions were understandable enough. In this sense, he felt there was a certain level of trust between them.

Kusla and Wayland followed the Knights’ style in salute, “Yes, sir.” It was a weak attempt to poke fun at the Knights’ formality, which Post heartily laughed off. His perspicuity was more than it seemed at first.

“Ah, yes.”

Just when Kusla and Wayland were about to step through the door, Post called them to stop.

“I do have to apologize to you regarding something.”

“Hmn?”

“I did try my very best, but there are some things that can’t be helped.”

“What is it?”

He answered the inquisitive Kusla.

“You’ll understand when you reach the workshop. Well, if you’re good at poison and assassination, there’s often a way.”

The two shrugged their shoulders.

“…Please excuse us.”

Wayland opened the door for them both to exit.

The subordinates carrying books along the corridor were lined up, their faces tense.

There was nothing to be hidden from a ruler who personally wrote his own papers.

Leadership often fell from glory because they of subordinates’ betrayal. Such rulers weren’t able to hide from their secretaries anything they wanted to keep secret.

On the other hand, Post could hide all his secrets and fabricate reports as he needed.

It seemed the land near the battlefield was not a place knights could calmly cleave their way through.

This building seemed to store all the things taken from the guilds in this town – perhaps even the building itself was taken just the same. Upon coming outside, they found the Knights’ flag cast high in the sky, declaring their authority unashamedly.

In the plaza outside of the building there was a bronze statue of a soldier clasping onto a magnificent sword, symbolizing the city’s independence, but it really held little more than ornamental qualities.

Whoever could swing the metaphorical sword to slay sinners was governor of this town.

However, the Knights wielded their authority to summon Alchemists and the authorities at the town wall who wouldn’t check their bags.

So, since authority made the natural order of things in this town, Kusla and Wayland’s fates were all decided by Post. The authority was wide in scope, and at the same time, heavy.

Kusla and Wayland went by the flag and the guards, narrowed their eyes in the midday sun, and stared into the bustling streets.

“What do you think?”

Kusla asked this to Wayland, who was speechless as they stood at Post’s desk.

Wayland was the type who hardly talked to Post’s ilk, though not because Post was someone he was unacquainted with. Instead, he was thinking of how to kill the other party.

This was something Kusla heard of 5 years ago when they were still wet behind the ears.

“I can’t tell with just that.”

“That’s true.”

“But it’s like mining. No matter the metal, God never gave it in its purest form.”

“In other words?”

Wayland gave a subtle grin.

“In other words, we continue work as usual.”

After finishing their lunch in the middle of the town market, Kusla and Wayland were off to this new workshop.

Since the city was so bustling where they stood, there had to be a quieter place elsewhere. They strolled along a stretch of empty houses, and their field of vision burst open after passing through.

An expansive urban landscape was right before their eyes, and the frothy sea stretched from afar and into the horizon.

It was beautiful.

They wondered about why the area around them was so devoid of noisy strollers, and realized thereupon that it was probably because they were at the face of the cliff. Some architectural beauty of an Alchemist’s workshop probably lied here.

“That’s quite the extravagant workshop.”

“That Thomas guy sure was something.”

A battle was meaningless if final victory was never won.

Kusla and Wayland would probably have to use unscrupulous methods to win their battles just the same, and only once they won would the costs be considered. If the production of one Alchemist alone was effective enough to overturn the entire battle situation, operating in plain site from a workshop among the citizenry (complete with this resplendent landscape) was a necessary evil.

Wayland grinned as he waved to Kusla from a distance. They went to the side of the workshop, looked down to the civilization below, and even Kusla was shocked.

“A waterwheel too?”

“And the water’s flowing through the ravine we passed. I think there’s a culvert dug deliberately under here, but it doesn’t seem that we have all the water to ourselves after all.”

Kusla followed Wayland’s stare and looked down to the bottom of the cliff, scanning below and catching glimpse of the harbor. There were several water wheels spinning, and various buildings gathered around them; it was difficult to tell if they were for flour mills, threshing, or some other craft though.

The strength of the waterwheel was decided by the water current, and the current was decided by the height from which it fell.

The workshop was built at the bridge. The place where Kusla and Wayland stood was the first level, the workshop took up two levels below, and the waterwheel was at the bottom. This meant that the full force of the water was down below.

Before now, Kusla had to cooperate with craftsmen to share facilities like the waterwheel. Considering his past, this was a luxury worthy of appreciation.

“The furnace is up to snuff. They actually built such a large furnace here, huh. Well, I guess they allowed it begrudgingly because it’s next to a waterwheel.”

“We can wash it off with the water if there’s a fire.”

Wayland turned to Kusla with a look of curiosity.

“Then the people below will be affected.”

Though, even if that actually happened, he would remain unfazed.

For an Alchemist, he fit the stereotype pretty well.

He would not care about the trivialities of others’ lives, and he still would not have much concern even if major events occurred to them. Kusla, who had realized Wayland’s removal from virtually everything else in the world, would sometimes think this way too, or rather, he was only concerned about these things out some nebulous sense of obligation.

“But what’s the thing that fat uncle wanted to apologize about?”

“Hm… what was it… I can’t think of it.”

They lifted their eyes away from the waterwheel and appreciated the beautiful scenery. Brightened by sunlight, the atmosphere allayed any sense of apprehension they might have felt about the situation.

“Maybe he’s just bluffing us. Let’s hurry in, it’s cold.”

“Right, let’s go on in.”

Kusla felt a little reluctant as he looked away from the cliff – not that it would be his last, but its unparalleled quality was alluring.

He came to Wayland, who was anxiously unlocking the workshop with the brass key they’d been given. The door opened, and Kusla walked right into Wayland, who had stopped abruptly, from behind.

“Hey, what’s with you?”

Kusla chided Wayland in frustration, looking past him to catch of glimpse of the inside.

The stone wall was lined with wood against the floor, and the walls were crammed with a seemingly endless collection of sundries – as though some psychotic inhabitant did the decorating. The room was certainly not dirty, but the amount of effort to maintain it all seemed questionable.

Kusla found himself more surprised that this would cause Wayland to freeze up.

The moment he’d thought this, a foreign voice spoke from the room.

“I see you’ve finally arrived?”

Past Wayland, the source of this voice resounded like an avalanche against the building’s thick walls, echoing with clarity.

The inflection of a voice often carried surprisingly more information than its content. An accent could betray an accurate impression of the physique or facial features of a person, and their elocution roughly betrayed the person’s status. A speaker’s disposition was most evident in their tone, as people’s emotions invariably carried with speech.

All things considered about the voice he heard, Kusla was able to deduce that the person in front of him was to be expected as an overseer for the two.

Until he shouldered past Wayland in the doorway. Kusla rubbed his eyes again – the sight too unbelievable.

What is this person doing in an Alchemist’s workshop?

There was a petite nun fully dressed in a robe that went to her toes.

Her robe had patterns belonging to a Knights-affiliated monastery along the edges.

She did not come in mistakenly. Probably.

“Who are you?”

Wayland prided himself in that if they were together, he would remain silent and let his partner handle the talking, while he would only focus on how to kill the opponent; at this point, he spoke in an unfriendly tone.

“My name is Ul Fenesis. I have been dispatched here by the Knights of Cladius.”

Here robe was white, with a veil covering the top of her head. She looked just like a doll, with wide emerald eyes and distinctly white bangs. It was not unheard of to see hair that was a sort of alabaster in shade, but it was definitely rare to see such eggshell white strands.

“I am here to watch over you.”

Fenesis seemed untroubled by Kusla and Wayland. After introducing herself, she rose herself up from her chair to stand. As to why there was no difference in height either when she was sitting or standing, it was because her feet could not touch the floor when she sat in the chair.

She was a child.

However, her expression suggested anything but childlike naiveté. She carried an air of boundless gravity.

Now what do I do?

Kusla turned to see Wayland obliquely over the shoulder, but any expression that was there on his face had long since escaped him.

“Should you do anything that deviates from God’s path, I will report it to my superiors. Please, do not forget God’s Teachings, do not break God’s Order, and do not sully God’s Prestige. You would do well to remember these three points as you work for the Knights – for God.”

Her manner was everything like a monasterial Induction Ceremony, but the troubling thing was that the nun before them, Fenesis, wore a gravely serious expression.

This girl, who was surprisingly smart for her age, was reminiscent of the fanatics Kusla ran across every so often.

Narrow-minded, honest in expression…

Post might have been apologizing for this. The Knights’ bureaucratic structure was not steady as a rock on land. It felt like confirmation of how this world consisted of three kinds of people: those who fight, those who prayed, and those who sowed.

The Alchemists hired by the Knights were part of the ones who battled, as they were basically involved in developing weapons or technology to break cities down. Alchemists would be registered under the “Baggage Teams” as they were needed to make various materials.

Nevertheless, Fenesis was clearly a vanguard of the praying lot. Given her position as a nun, she was probably a member of the Knights’ Choir. Of course, they were different from The Church’s Choir. The Church’s Choir would praise God in a silent chapel, while the Knights’ Choir exalted in the midst of a sanguinary battlefield.

The nature and direction of organized faith was different from what the Knights’ Choir had. It was hideous and power-oriented. Their forced lied in wait to strike, hoping to steal the Battle Corps’ authority. The Church and even its allies were eager to take Alan Post down, so a wounded Knights of Cladius might be left hobbling in a forest of predators. If the Knights’ “spare” Alchemists were killed as well, they would look for an opportunity to take control of Gulbetty.

The more troublesome thing for Kusla was that, though the Knights’ Choir were a part of the Cladius Knights, they had always viewed Alchemists as their mortal enemies.

The people of the Choir sincerely thought that they were existences that defied God, and had to be erased from the land.

They had yet to discover who killed Thomas.

This meant the killer could be hiding inside the organization.

“And your answer?”

Fenesis lifted her chin as she asked.

He recalled how a certain wretch of a nun at the nearby monastery years back would punish him by slapping his face with a cane.

For such a determined people, first impressions were key.

As Kusla considered this, he started to reach his hand out.

Wayland, who had been imitating a statue before now, sprung forward and offered his hand first.

A handshake.

Surprisingly, he seemed to have the same idea. Fenesis looked surprised, but still reached her hand out to return the gesture. That was a human response.

However, Wayland’s hand went past hers, and soon met its objective.

The nun Fenesis widened her eyes as they caught sight of Wayland’s incoming hand.

The hand that twitched all its five fingers in a singular motion bound right for her chest.

“Hm?”

Wayland shifted his hand around with a discontented frown, looking as though he did not find what he was looking for.

He went to confirm it again, the other hand outstretched.

Fenesis recoiled from Wayland’s second incursion and swung her hand at his face.

“Humph.”

Wayland effortlessly bent back to dodge.

She did not show any reaction – not because the slap was evaded, but rather, because her brain had yet to process what had just transpired. Kusla, too, was stunned by what Wayland did.

Her slap seemed to be an instinctive reaction.

However, could not well maintain her balance due to the sudden dodge, and Fenesis staggered greatly before she fell against Wayland’s chest.

“–!”

All at once, she seemed to regain control of herself.

She pried at Wayland’s hand, hoping to escape his vice-like grip.

Wayland’s grabbed onto Fenesis’ slender arm, and the difference in strength caused her body to jerk.

“What are you doing–”

Fenesis’ frantic protests were so high-pitched that Kusla barely understood her her.

Wayland, who was holding onto the nun’s arm pressing against his chest to push him away, used his other hand to cover the girl’s face, ostensibly trying to seal her mouth. The little face was covered completely by his hand, and Kusla gasped without a second thought.

Proceeding, he brought the wide-eyed Fenesis level to himself, intent as though he were trying to see into her mind.

“This is an Alchemist’s workshop. It is rather–dangerous for a child to roam around here.”

“Gh– Ugh!”

Wayland might have seemed scrawny, but he did train his body better than those roadside mercenaries for the sake of his metallurgy. He stood tall and steady no matter how Fenesis struggled.

Her mouth was shut, and her eyes dared not shut for a moment; it was an instinctive fear – that her skull would be cracked.

Wayland wordlessly focused his stare into Fenesis’ eyes. She continued to writhe about, but she could not move half an inch beyond his forceful control.

Her body quivered, most likely out of fear rather than any struggle.

“Humph.”

Wayland then let out what sounded like a bored snort, and took his hands off her.

She stumbled back, wide-eyed, and shakily remained standing for mere seconds before collapsing onto the floor, desiccated.

Kusla had no need to look up to sense Wayland’s gaze.

“I’ll go into the workshop here. Handle the rest.”

He went and quickly descended the staircase.

It was already too late by the time Kusla realized he had gone overboard.

However, the good in it was underscored by the most basic of basics in matters of human association.

If someone instilled overwhelming fear or thorough discomfort in a victim, it would be easier for a third person to get close to that victim. Fenesis had bad luck when she introduced herself as their monitor, and Kusla was fortunate not to do anything back then.

Wayland took on the role of the antagonist, and pushed the troublesome Samaritan’s role to Kusla.

Even so, Wayland grabbed her without hesitation, and threatened her without mercy. His mental state was truly terrifying.

Kusla had no other choice.

It was impossible to try and salvage matters. He could only sigh and act as the third character. Since the pitiful girl came as a member of the prayer group in the name of supervising them, it meant that she was made the monitor of the workshop, and it had nothing to do with her will.

Despite her humiliation, she would come by the next day, and the day thereafter.

If he did not patronize her well, he would be unable to carry out his work well.

This wasn’t to say Kusla felt no annoyance about the situation.

Seeing her, he chastised himself for being unable to take action, and knelt down beside the small nun who let her tears roll silently down her cheeks.

Fenesis let out a sob, backing away from him in fear.

“Are you alright? That man’s a little weird in the head.”

It would be the first line of a long, long consolation.

| Back to Prologue | Return to Main Page | Forward to Act 2 |