Minato no Hoshizora: Part 3

A sensation of fresh coolness erupted within the boy’s shallow breast, and his consciousness stirred; awoke.

It was sunset, the sickroom sinking into the evening quietude. There was not a sound to be heard, not even the chatter of the television set, which, though he had no recollection of ever turning it off, lay dark and still.

He pulled himself upright on the bed, cross-legged. He was no longer dressed in his prince's outfit, but rather in the hospital's pyjamas. Before him were scattered the ten or more crystals of potential he’d collected. He eyed them, and a thought slowly framed itself, with a certain concision: The earnings of my labour.

He was growing used to these moments of sudden wakefulness. What had woken him up this time, he wondered. The first time this had happened had been because of the light of the meteor shower, the next the glow of the potential crystal that Elnath had been hunting, and the time after that, that girl’s gaze. Today, however, there didn’t seem to be anything around that could have done that to him.

He could still feel the sensation of pleasant coolness in his chest. Now it began growing, reaching through his limbs until it seemed as if he was being submerged in a pool of cool, invigorating water. No, he thought. Something’s definitely about to happen. He had been acted on by fate, destiny, whatever you called it often enough that he could recognise the signs of its movements. Something was about to happen, to come to fruition. And it would happen very soon.

Would it spell good for him, he wondered, or bad?

In the time since his encounter with the girl, when he had experienced for the first time in his life what it was like to be a prince in another person’s eyes, Minato had come to learn that the potential crystals were not without their dark side, and that he himself could not afford to approach them naively; that his and Elnath’s hunt for potential crystals was not something so clear-cut and simple that you could rush into it without considering its consequences. Those very consequences were weighing Minato’s thoughts down – until, that is, this sudden, refreshing impulse.

What was the presence approaching him now? He found that his heart was pounding. As he awaited its arrival, he, like always, trawled backwards through his memory for the events that had transpired up to this present moment. A flood of memories came surging back up in answer.

Potential crystals, it turned out, resided in quite the variety of people.

Elnath had said that most of them would be found in the hearts of small children, and this turned out to be the case. All it took to knock the crystals out of them was usually just a careless word or the lightest of arguments; and then there the crystals would lie, their possibilities never to be fulfilled, like the fragments of a shattered dream.

Buried in the hearts of adults too could be found potential crystals. A manuscript might be turned down or a painting refused for exhibition – or a program might be not taken part in, a train not ridden – and there, glowing forlornly on the ground, would be a potential crystal.

Elnath, of course, didn't think too much about it beyond the fact that the crystals could be reused as energy for his ship. To Minato, there were times when the crystals seemed to shine with a sickly, almost tearful glow, but Elnath’s answer to that, invariably, would be a cheery “Oh, don't worry about it” as he stowed the crystal away.

And really, Minato understood why he’d say that. It was like with the electrons again: just as they were always able to jump up to a higher orbit after falling, people might also always be capable of finding new things to aspire to.

But still the hollow feeling in his heart would not abate. He himself had given up on a great many things: on playing out of doors, on going to school, on after-school snacks with friends. On going on family vacations, on binge-reading through doorstoppers, on keeping a pet, on taking long walks; on going to beaches, or even just to swimming pools, on playing videogames so late into the night he'd fall asleep right in front of the screen, or on stuffing himself absolutely full with all his favourite foods. Not a single one of which he’d chosen himself to give up on. There had never been a choice at all.

But they were different! he’d think bitterly. If they wanted their paintings to be shown at an exhibit they could just try for it! Could just try for it, and worry about rejection when it happened. They were the ones with the stamina needed to finish a painting, and the ones with opportunity right before them – they could do it! If they had someone they wanted to see they could just jump on a train and be off! They could walk without needing help – they could ride on trains without getting sick from the shaking – they could just up and go!

He might not be able to do any of these, but they could.

So why, he wanted to shout, why not just do it?

Why, if it wasn’t an issue of whether you could do it or not, but rather one of whether or not you would, wouldn’t you just try and try and try until you had it?

“They don’t know how lucky they are,” he found himself muttering one day, after they’d collected a crystal from a girl, a high-schooler who hadn’t been brave enough to ask an older boy she’d liked out – and where had that gotten her now? Huddled on her bed, blankets clamped over her head. The skies overhead were veiled with the melancholy oranges and scarlets of the setting sun. Minato sat with his legs dangling over the edge of an office building, watching the sunset; beside him Elnath tossed his bag of potential crystals janglingly on a palm, assessing its weight.

No, they didn’t know.

“They’ve got every chance in the world and they don’t take it,” he muttered again; and at this a faint smile, tinged red in the light, tugged at the lips of his friend. He answered:

“Maybe that’s just how you see it, my prince.”

“Now, what’s that supposed to mean?” said Minato, eyeing Elnath.

But his friend shook his head lightly and turned away to look at the sunset. “Nothing. Only that you might be the one all ignorant of things instead. Like a prince in his ivory tower.”

“Huh?”

Elnath shrugged off his incredulous huh. “How serious a problem seems always depends on how the person is feeling,” he said. “You know how you people have this wonderful custom of giving up your seats for the weak and the elderly?” He swept an arm out into the sunset as if to say, Now, imagine! “Say you have a full bus, and an elderly person gets on. You might have some people just get up quite instinctively and offer their seats, of course. But you’re also going to get some people who might have been told off in the past for treating people like old fogeys, who hesitate. Other people might get so embarrassed at the thought of attracting attention that that they can’t even stand up. Sometimes, even just a simple act like offering up a seat is more complicated than it might initially seem.”

“Yes,” said Minato, “and?”

“And even just this one emotion of embarrassment varies from person to person. Some people might be able to handle this situation just by averting their eyes and looking down, but others might be panicking so much that it feels like their hearts are going to stop. They might have it so bad they have to get off at the next station, and then, at that very moment, get caught up in a freak accident of some sort that overturns their lives completely. Is it really fair to for anyone to say that they must still put up with their embarrassment and offer up their seats, then?”

“That’s a horribly exaggerated example, though,” said Minato.

“But is it really?” countered Elnath. “The world is full of exactly such possibilities. What to you might seem like a petty concern might well be a question of life or death to others. And that’s something you should definitely keep in mind.”

Minato pondered this matter. He himself, he thought, was always standing on the brink of life and death. Only in his case it wasn’t just a figure of speech. In order to extend his life by even one more day he’d been forced to lie in this hospital and give up on experiencing far too many things in life, and seeing people just giving up on these experiences without even trying made him fume. But looking at it from the other side, perhaps everyone else, who despite being in no danger of death, had things that they could never do “not even to save their own lives”. And if they did, assuming of course that they did…. He thought of the girl, the one who hadn’t been able to tell her feelings to the boy she’d liked. Perhaps for her, death would have been a pleasanter alternative to being rejected and having their friendship turn sour. And perhaps death really would have ended up being an outcome, if things had turned out very, very badly. Did any one of them have it worse? he wondered. He, who’d had to discard every free choice in his life to avoid death, or they, for whom death was always a potential outcome of their choices?

“But even so,” said Minato in a low voice, his face turned away. “I’d make the choice. Even if it was the wrong one – even if its consequences turned out to be disastrous ones. I’d want to make my own choices for myself.” He broke off and said again, in a soft, bitter tone, “Oh, I’d sure want to. That’s the one thing that I can still do in this pathetic, bedridden state.”

Elnath smiled gently. “Well, everyone’s limited some way or other,” he said. “At least, when you’re under the fundamental laws of this world.”

Elnath’s words made quite an impression on Minato.

“This world, you say…” said Minato slowly. “Does that mean that there are other worlds as well?”

“Precisely so,” answered Elnath.

“Even one where I’m not sick like now?”

“Even them.”

“Is it possible to go there then? With your technology?”

Elnath nodded. Then, looking solemn, he said, “But the question is how this new world should differ from our own.”

Minato waited silently for Elnath to go on. His friend, after taking a deep breath, turned to face the sunset.

“You, of course, would like to go to a world where you’d be healthy and free.”

That was certainly true. “Right.”

“The problem is that it’s not as simple as it seems.”

“Why not?”

“Because there’ll already be a healthy you in that world,” said Elnath. “ Unless you somehow manage to find a way to replace the other you’s existence with your own, or to fuse your existences together, or something along those lines, that world would simply refuse to accept your existence and throw you right back out. Really, I’d say that the only way you could have your healthy life was to have started it already healthy…”

“Oh…” Minato slumped back, crestfallen. “Well, if only there was a way to turn my time back to the beginning…”

He felt Elnath pat his back. “Even that’s just a question of probability,” his friend said. “For all we know, there might actually be a way for you to start it over again somewhere out there.” He hesitated, then, mustering every ounce of cheeriness he had, added, “Besides, when you’re with me you’re just as healthy as anyone. Freer than anyone – you can even fly! That’s already pretty good if you ask me.”

“Right,” said Minato. “I guess that’s true.”

The prince’s face lightened up a little in the ray of the possibility before him. Now the boy who’d cast his magic on him leapt to his feet. “Guess I should get to work as well,” he said, pulling a stretch.

“You’re going out to collect more?” Minato asked.

Elnath jumped, blinking rapidly. “W-what?” he said, suddenly waving his hands, flustered. “N-no, no. I mean, well, it’s not exactly crystals I’m going out for, you know, but…”

“What?” asked Minato, tilting his head.

Desperation flashed across his friend’s face – suddenly a pair of hands clamped themselves on both sides of Minato’s head; and, before he could react, began wildly messing up his hair. And Elnath was crying, “Sorry, gotta go!”… and then he’d made good his escape.

The tousle-haired prince took a moment to gather his thoughts and realise that his friend was gone. Then he leapt out into the air after him, crying “Hey!”, his lips breaking out, despite himself, into a smile.

Another night. They had come to a smart-looking panel-built house, aqua-blue blinds half-lowered, and therefore half-open, at the windows. Gliding smoothly through the air like swimmers, the two boys approached one of the windows on the second floor and looked in.

Under an all too bright lamp sat a kindergarten-aged boy on the floor, his face downturned and hidden in shadow. Placed all around the small space were colourful cubby boxes, their shelves filled to brimming with toy cars, robots and trains. This was evidently the boy’s room.

The boy was speaking, in a disconsolate and quiet voice.

“I know.”

Around the boy’s loose and airy head swung the yellow candy-crystal, the potential crystal.

His mother stood calmly before him, oblivious to the crystal. “Kazu, you're a boy after all,” she said. “There're plenty of jobs out there more suited to boys, you know.” Her voice was a coaxing, firm, nagging wheedle.

“I mean, what the teacher said wasn't in any way wrong – you are a sweet boy, and kind and nice, of course you are. But wanting to become a florist when you grow up, you see, just isn't what most boys are like.”

“I won’t anymore,” whispered the boy, his voice shrinking to an almost inaudible undertone.

The mother heaved a great sigh. “Yes, I know, there are some men who become florists too. But you see—”

“I won't anymore,” whispered the boy again. All at once the arc of the crystal's orbit had grown larger. Faster and faster the crystal spun, until it seemed as if it would fly off at the very next moment. The mother was continuing on: “I mean, there’re plenty of jobs you could go for. You could be a fireman, for instance, or a driver—”

As she paused to draw breath, the boy said dully, “I’ll say that next time.”

“That’s my boy,” the mother said, relieved.

And at that very instant the crystal flung itself off its orbit and outwards, flying clean through the wall. Minato gave the signal.

“Now!”

Elnath caught the crystal deftly.

“Got it!” he said. Satisfiedly, he put it away in his pouch, then shook the pouch, to the sound of clinking.

But even though they'd succeeded in acquiring a crystal, Minato was filled with misgivings. The crystal sitting in Elnath's sack was – had been – the dream that the boy had given up on – the potential he had to become a florist. And now it also meant that the doors to every other job considered ‘womanly’, makeup artist and ballet dancer and gourmet advisor and handicrafts teacher, were closed to him. Up until this point the boy might have lived with the conviction that there was nothing he could not be, but now his mother taught him the knowledge that that there were things that one could be when one grew up that were considered right and proper, and that there were things that weren't. A knowledge that some people might call a part of growing up, and others might call nipping the boy’s potential in the bud.

And Minato? He could not say which it was. But the thought lay heavy in his heart.

And if the mother had been able to see him – Minato, in the prince’s outfit that, in Elnath’s words, was a reflection of his inner thoughts and desires, this overwhelmingly non-masculine outfit of his that happened to have giant star earrings dangling from each ear – would she also have called him girly and shameful too?

Just what was wrong with becoming whatever you wanted? Minato thought fiercely. If you had feet you could walk on and hands to work with, the strength to handle a long day of work and friends to talk and laugh with, then ― what did it matter what job you chose?

He wondered, too, whether that mother would have preferred a son that was bedridden all day long, or a son that had become a florist and was enjoying every moment of his work to the full.

“We’re leaving,” called Elnath, rising back up into the air. And Minato, glancing helplessly again and again at the room, could do nothing but follow Elnath away.

At another opportunity, Minato was able to bear witness to how a potential future might come to be lost, without the person even being aware of it.

It was to the sixth floor of an apartment block that Elnath brought him, saying, “This one’s gonna be a big one.” Looking in from the balcony could be seen a room with bed and desk, and female idol posters on the walls. And lying belly-down on the bed was a skinny teenager who looked, as far as Minato could tell, to be about the age of a high-schooler. This high-schooler was resting his chin on a palm, absorbed in something he was reading.

Elnath put a hand on Minato’s shoulder, leaning in to peer at the reader. “What’s with these books with all those quadrangular designs?” he asked. “I’ve seen them everywhere.”

“Oh, you mean manga?” A bestseller, too, with an anime adaption ongoing.

“Oh, so manga’s what it’s called,” said Elnath. “I was wondering why postures of the characters keep going through all those changes. And the visual arrangement of the words, too – how artful! It’s fascinating how you people manage to turn even the words into an element of the page’s composition.” Elnath was frowning intensely as he spoke; seeing him, Minato had to bite back a smile.

“The panels each represent a slice of time,” he explained. “You read them in order, like watching a movie, so one person has to be drawn many times moving through his different postures. And the words are just sound effects and dialogue.”

“Woah!” cried Elnath, flinging up his arms in amazement. Driven by the inertia of his motion, the tails of his scarf followed suit, flying up to join his arms like a second pair. “That’s amazing! That’s absolutely amazing! It’s cool enough that you have a way of displaying three dimensional objects on a two dimensional plane, but to think that you can also represent the time axis with these simple drawn lines, when we ourselves wouldn’t be able to access it without four dimensional manipulation! What madne...” He caught himself. “You really are a incredible race, you know,” he said instead.

“T-thanks,” said Minato, caught off guard by Elnath’s enthusiasm.

“This boy must be quite something, to be so absorbed into a work of such complexity,” Elnath mused.

Well no, thought Minato, he probably just liked the art and the story. Nothing at all to do with any complexity about the nature of the medium or whatnot. But explaining any further seemed like a pain, and he kept his mouth shut.

All this while, the high-schooler kept on reading, sometimes biting his lip or scratching at his head, his eyes never leaving the page.

And then Minato noticed something. Approximately five steps of distance between the bed and the desk hung a mass of light in the air, languidly drifting back and forth in place. The mass threw out a green-gray light, which grew and shrunk in size as it moved.

“It’s out of the body already,” said Elnath, pressing his palms together in excitement. “Look at it wavering!”

“That’s the potential crystal?”

“Yep. See how the light’s coalescing as time passes? Eventually it’ll hit a critical point and then there’ll be no going back.”

“No going back?” said Minato. “But he’s not even doing anything at all.”

Nothing besides reading his manga. He hadn’t even bothered to unpack his bag, which had simply been tossed onto his table, and his socks had just been left balled up on the floor.

Elnath glanced his way. “Some decisions are made by not doing anything, after all,” he said. “Look, the light’s getting stronger and stronger. He’s going to lose this particular potential he has without even realising it. Nothing more frightful than unawareness in action, eh?” At this moment the high-schooler gave a short bark of laughter. Maybe at a particularly funny scene in the manga? Minato creased his brow at Elnath’s words and asked,

“You mean to say that he’s lost some potential because he’s slacking off rather than studying?”

Though that sounded too preachy, he thought. That line of thought ran uncomfortably close to the one of “if you don’t study hard and get into a good school you won’t be exercising yourself to your full potential”, a line that forever seemed to dangling from the mouths of parents and zealous teachers. But Elnath was rapidly waving his arms in negation.

“Oh no, no, no, nothing like that,” he said. “What he’s done, and all that he’s done, is make the decision not to study. This isn’t something that’ll necessarily end in bad consequences.”

“Oh? Then tell me: what good consequences might it lead to?”

“Oh, you know,” Elnath said. “Maybe something in this manga will leave an impression on him and inspire him to walk down a path that eventually leads him to happiness and success.”

“Now that’s just ridiculous,” said Minato.

Elnath snorted. “Maybe. Well, either way, all that this crystal means is that he’s lost that state of in-betweenness between studying and having fun.” He grinned slyly. “Though given the size of the thing I can’t imagine its influence being small.”

The light was continuing to acquire consistency. By this point it had become like a focused ball of torchlight, and a long way off from the dully shining cloud that it had been.

“How does the crystal know what sized light to give off?” Minato asked. “It exists in the present, doesn’t it? How can something in the present know about what happens in the future?”

“Now that’s a real philosophical question.” Elnath folded his arms theatrically, adding two nods for proper dramatic effect. “The answer? It’s a sign of just how high-order the potential crystals are.”

“N...nooope, don’t get it.”

Elnath put on his I thought so face, and shrugged his shoulders. “Beings that exist only on a plane have no conception of height,” he said. “Minato, remember when you were flying in the air? With the whole world spread out before you. Suddenly, you’d gained the ability, for instance, to see what was happening on both sides of a high wall.”

“Right...”

“You people perceive your world in three dimensions: length, width, and height. There’s also the time axis, but you with your limited senses cannot perceive it in its entirety: you can neither return to the past nor know of the future. Potential crystals, however, answer to an even higher-order logic than the ones in these three dimensions, and so in essence have the entire time axis spread out in full view before them. Well, basically this means that potential crystals are privy to every turn and resulting event of destiny in this world. That’s why it’s possible to determine the sum of a crystal’s potential from the light it gives off.”

“And by destiny, what you mean isn’t “fate”, like you once said it was, but more something along the lines of cause and effect?”

“Something like that, yeah.”

Now Minato was beginning to understand why Elnath had been so amazed by the manga. Manga was two dimensional, but somehow managed to fully incorporate the four dimensional axis of time. And then it’d be read by three dimensional human beings, who, whenever they didn’t understand anything, could simply flip backwards to some earlier point of time; or, if it ever got too boring, skip ahead into the future. However unorthodox this way of perceiving manga might be, the fact was that manga could very well be capable of simulating the experience of seeing in four dimensions.

“It’s a bit like what Plato was trying to say with his analogy of the cave,” Elnath added.

Plato. Even Minato had heard of the name of this famous philosopher. “I had no idea that your ship was using something so amazing as an energy source,” said Minato.

His friend reddened a little. “Well, now you know,” he said. Then, to himself, he muttered, “Still powerless to stop our destruction though.”

Minato started and looked at Elnath with wide eyes. “Destruction?” he said.

Realizing that he’d said more than he should, Elnath clamped his hands over his mouth.

There was nothing for it, though: after bearing the brunt of Minato’s stare for a few moments, he came to a decision and took his hands off his mouth. He breathed a slow breath out.

“Yes, destruction,” he said. “That’s the fate that awaits our planet at the end of every single possibility, down every potential future. Not a rosy prospect, eh?”

“Is that why you left on your spaceship, to leave your planet?”

“Not exactly. What we are escaping is more precisely the very destiny that decided our planet should be destroyed—” He broke off suddenly, to say, “Oh, look, the crystal’s coming.”

And then all opportunity for conversation was cut off as the crystal came flying at high speed out of the teenager’s room. It slipped past Elnath’s grasp—

“It’s yours, Minato!” cried Elnath.

“Ah, ah...” Stretching an arm up high like a ball fielder, Minato caught the potential crystal. His palm smarted slightly from the impact. “Got it.”

“Ooh, it’s a big one!” said Elnath, taking it from Minato. Hurriedly he unslung his backpack and slipped the green-gray crystal in.

Minato took one more glance at the room. Now the teenager was lying on top of his manga, fast asleep. Quietly, Minato made a wish for this unfortunate teenager, that fate might not lead him to too unfavourable a future.

Still feeling the impending sense of something approaching, Minato took the potential crystals he’d earned from each of these encounters and made them float up into the air. He’d acquired the ability to do so after a period of collecting the crystals. He was still a long way from being a fully-fledged magician, of course, but with his powers he could perhaps pass as the apprentice of one.

He applied his powers again. Gone was the evening lethargy of the sickroom, to be replaced by absolute darkness. He raised an arm. Now he opened his palm wide, and an uncountable number of stars bloomed into being on the sickroom’s walls.

Except now it no longer was the sickroom. The darkness before Minato had a definite dimension to it, and the stars and constellations now around him were sitting in the all their proper positions. The very best planetarium could not come close to replicating this experience. This was space, the real thing.

And in the middle of it all sat the magician’s apprentice, who gave a single, satisfied nod.

This way, he thought, even the invisible stars are present. I wished for them to be present, and now they are. Stars from the sixth magnitude to the tenth, all the way to even the fiftieth. All of the stars that had been shining all their lives without a chance of discovery.

And Minato was one of them, another star that could never be noticed in human form. He raised a finger, around which the glowing potential crystals gathered. He imagined himself as their star, and the potential crystals his planets. And now the lights began to move around him, slowly at first, their trails tracing out arcs of orbit. Then faster and faster they began to spin, as his premonition of something approaching began to beat in an increasingly urgent rhythm. And at last, when the stars were whizzing around at an audible speed, he heard a sound at the door.

There was a click as the door cracked open – and then light blasted into the room. Minato cried out in surprise and let the crystals fall back onto the bed, blinded. A hand went to cover his eyes against the light; at the same time he was turning instinctively to see what was at the door.

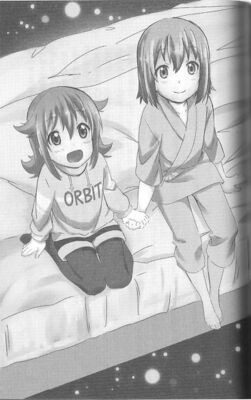

There was a small figure there. He couldn’t make up the features against the light, but it seemed to be a young girl still in early primary school.

And then the blinding light was gone. The girl didn’t seem to have moved, but now she was standing inside, with the door shut behind her.

“What’s that?” said the girl to herself.

She looked around the room with wide, wondering eyes. She had on a light brown coat. Her bright coloured hair was an unruly mess, and her eyes were big and lively.

Maybe she was trying to make sense of where she was. Her attention was caught by the sight of the stars stretching endlessly through the space in the room.

“Wow...” she breathed.

The curiosity that burned in her eyes was brighter than any star.

And then Minato knew. This must be the girl that had been looking at him, back when they were in the middle of a crystal hunt. Quite easily, without thinking, he spoke.

“Who’re you?”

The girl stiffened, only then noticing Minato’s presence. Her shoulders sank. Distress was showing in her eyes as she stared wide-eyed at him, stricken by her guilt from opening this door without asking and seeing something clearly not meant for her eyes. She shrunk into herself, as if expecting he would yell at her.

A faint smile made its way to Minato’s lips. “Come over here,” he said, patting a spot on the bed.

He’d been hoping for a response, but the girl only continued to stare up at him, not moving. He felt his heart sink. No, he told himself firmly. If this really was the girl from before, then, surely, fate had bound them together. They had to be; why else would she have been able to see him back then? They had to be fated to meet.

He summoned his strength and spoke again. “This is space.” Confident, but friendly. “You can see better from over here. Come on.”

The girl inched forward slowly, looking like a frightened puppy. There was an unfamiliar smell in the air, a hint of something like sweet candy. Moving hesitantly across the ocean of stars, she eventually neared and reached out with one hand, touching the bed. The solidity of it seemed to reassure her, and she turned her head to look around her again. All trace of unease had vanished from her face. Now she wore the same expression she had on that night. Her lips sat slightly parted as she took in the sight of the universe all around, her excitement so great she was forgetting to blink; and her open eyes gleamed like fires.

“Sit here,” Minato said, patting the bed again.

The girl blinked, mute, and planted herself judiciously on the very edge of the bed. She kept her gaze fastened firmly downwards, not daring to meet his eyes, although that didn’t stop her from stealing peeks up at him.

She didn’t recognise him from that night, he realised. Not now when he wasn’t in that fabulous outfit of that night any more. And in all fairness to her, it would indeed be rather difficult to see this hospitalised patient as the same prince that was soaring in the night sky.

He took up the crystals in a hand and cast them, with a flourish, into the air. The light of the crystals shone forth; and then, as if drawn by it, the stars rushed in to surround them.

Now the space around them had become a complete entity. The stars began to streak backwards behind them as they watched, sitting on the bed flying through the field of stars.

She gave a soft cry as she watched this scene before them, the stars zooming past like they were riding on a roller coaster, her voice at once filled with wonder and with an awed fear. And then she breathed again, but this time only with wonder.

“Wow...”

Her wonderment at the scene’s beauty seemed to have triumphed over her fear from their flight. She gazed enraptured at the sky above, and, as if to anchor herself, reached out unconsciously to take hold of Minato’s hand. Her hand: it felt, to Minato, a little like heated jelly. It was a yieldingly firm, smooth sensation, beneath which he could feel a gentle, glowing warmth. In that same instant he was suddenly intense aware of every sensation his skin was feeling, while simultaneously feeling as if his thoughts were draining into a slow batter.

He’d been touched aplenty by the doctors and nurses, but somehow this touch felt like like his first, virgin touch of skin on human skin.

The girl still sat, entranced by the immensity of stars spreading before her eyes. Minato could not help but smile. Who would have thought that what he did could have been able to impact someone so strongly? That he could have been of use to someone, as he was now?

With her he could become a prince for real. He might be wearing only pyjamas and be stuck in a hospital, but he would do his best to become a prince for her.>

But was it embarrassing to call yourself one!>

He laughed softly under his breath and turned to face the girl, wearing a wide grin. He tapped the back of her hand.>

“It’s all right,” he said, a little teasingly, the sound of his voice making her head whip back towards him. “I can use magic.”>

She stared at him, wide-eyed, her cheeks growing red – even redder.>

“Do you like stars?” Minato asked.

The girl nodded – not once, but five small bobs of her head.

“Do you know the Summer Triangle?”

An moment of hesitation; then the girl answered,

“I know. Orihime and Hikikoboshi, and also Cygnus.”

“Right,” said Minato, laughing softly, “You’re right, though you’re mixing up your east and west. Did you know that there’s also a Winter Triangle?”

“No...” she said, trailing off.

“Alright.” He made an act of rolling up his sleeves and pointed a finger straight ahead. “Forward in that direction!”

Just as Elnath had taught him when he’d learned to fly: to will himself strongly in a direction. He himself didn’t know whether the bed was actually moving or whether it was simply the stars speeding behind them that gave that impression; but at his words the bed accelerated with a start.

“Oh!” cried the girl delightedly. “Oh, oh, oh!”

And watching her, Minato realised: her happiness made him happy. Her fun was his fun. Her joy was his joy.

The fire that burned in her eyes as though they had caught the starlight, came the thought, was surely no greater than the fire that burned in his own, when he watched her.

Constellations swam into view ahead of them, beyond the lines of the fleeting stars. “Look over there,” said Minato. They could make out the three points of a rough equilateral triangle: Sirius from Canis Major, Procyon from Canis Minor, and Betelgeuse from Orion, through which swept an expanse of the Milky Way grander and more beautiful than could ever be seen on Earth.

“Oh, it’s true!” cried the girl delightedly, dropping a fist into her palm. “It really is a triangle! I always looked for Orion at night, but I never noticed.”

“It’s also part of what’s called the Winter Diamond[1], though it’s really a hexagon,” added Minato. He had to fight to keep the pitch of his voice from rising. He would never have been able to experience such happiness in the same circumstances if he were alone. But now the world was beautiful and there was someone here willing to listen to him talk. And as another surge of happiness broke over him, stronger than all the lights of the galaxy, Minato’s attention was caught, for the briefest moment, by a small, V-shaped face in the sky near the Winter Triangle – the constellation Taurus, with its beta star Elnath.

It looked like it was smiling down at them.

The girl kept on coming back visit Minato.

He continued to experience that sudden surge of clarity prior to the door opening. It became a sign that he should immediately transform the room into space again; and moments after doing so, her small hands would pull open the door.

He grew afraid, sometimes, of how his world would retreat into a blur when he was not together with the girl. With effort he could dredge up his memories of those times, every hazy moment right up to her opening the door, but they would always feel distant, like trying to remember something from long ago. As if the times she was not with him were nothing more than a pale, evanescent dream.

And that was fine, Minato felt. His waking hours weren’t spent on anything other than lying on his bed and receiving the occasion checkup anyway. While he was indeed able to while the hours away with his books and TV, of peers he had none, except for the girl. So as long as the girl did in fact come to visit, he thought, what did it matter that the entire day passed by, blanked away? Even if his memories became uncertain, even if he no longer knew what day it was, as long as he could be the girl’s magical prince, he could, for a time, shed his role of the tree in the forest unknown to man.

He found that he was beginning to believe in fate.

There had to be some power at work between them, he felt, for him to always be awake at her visits. Elnath had called this power ‘cause and effect’ – and in classsical physics there had likewise been the concept of causality, which had been considered a fundamental principle of the universe. Causality dictated that every given result had to have its corresponding cause somewhere further up the line, and that as you chased a single cause further and further backwards through time, the influence that that one cause could have on the entire universe became greater and greater, farther and wider reaching. This was the simple fact of things, a property so fundamental to the universe that it simply couldn’t be circumvented or annulled. But if, far beyond the reaches of relativity or quantum theory, there was a being out there somehow manipulating these threads of fate, then Minato was most grateful to him. For in bringing Minato and the girl together, he’d proved that Minato was no longer a lone tree in the forest, but instead was a person whose words were heard and whose presence mattered, who, at long last, had been able to form a genuine bond with another human being.

Deep in the darknesses of space, the two children sat together and talked. The bed carried them, their steadfast ark, across the ocean of the stars.

“It’s so beautiful,” the girl said. She lay with her back on the bed, taking in the vast expanse spread out before her eyes. “I could never ever get tired of looking at the stars. Sometimes when I look up and see a sky full of stars, I almost feel like I can even hear them making sounds as well.”

That’s the way I feel when I see you, Minato thought. Her face was such a kaleidoscope of expression and life that he could look all day and never grow bored. The sound of her voice rang as lovely to his ears as bells.

Suddenly the girl began to sing.

“That’s ‘The Song of the Stars[3]’,” said Minato in surprise.

The girl sat herself up and looked at him quizzically. “The what?”

“What you were singing just now.” Minato said.

“I don’t know,” said the girl, “I just learned it from my grandma…”

“It’s a pretty well-known song.”

“All I know,” she said, “is that it was written by the person who also wrote the Galactic Railroad and also some poem about being fine in the rain.”

“The Night on the Galactic Railroad and ‘Be not Defeated by the Rain’,” said Minato, correcting her. “And the person’s name was Miyazawa Kenji.”

“Right, him!” The girl waved her arms in delight before bending back to look upwards again. Her expression turned pensive, still retaining its smile. “The Song of the Stars…” she sounded out the syllables. “It fits. Did you know that there’s a clapping game to this? Me and my friends play it sometimes.” She began to sing again, closing her hands into fists and striking her palms to the rhythm of the song. Oh, see the ruby eye of Scorpio...

Minato watched her actions, fascinated. Into his mind sprang an image unbidden: a group of girls sitting down to play this game. They reached out to take hold of happiness with one hand, pounded out sadness with the other, shaped their dreams into wings to fly on, made glasses with their fingers to see the true state of the world with. Chattering, laughing, wearing wide smiles of delight…

“Want me to teach you?” asked the girl, turning her head to look back at him with a smile.

“What? Oh, no, thank you… ” Minato shied away from her earnest gaze, keenly feeling his lack of experience with friends. He changed the subject. “Anyway, I was thinking about what might have made Miyazawa Kenji write the song this way.”

She did not notice his internal struggle. “What’s wrong with it?”

“It gets so much about the stars wrong,” Minato said. “And that doesn’t make sense, because Miyazawa Kenji knew plenty of geology and astronomy, so he must have known that it was wrong.”

“Wrong?” she said.

“Yes. For one thing, Antares, the alpha star of Scorpius, is its heart, not its eye. Procyon, the alpha star of Canis Minor, is also its heart and not its eye. And it isn’t even blue, anyway.”

The girl deflated a little. “Oh, that’s true, isn’t it…”

Minato continued on. “And wasn’t there a line that went looking high above, the little bear spies/The shining spindle of the heavens?”

“Yes, at the end of the song.”

“Well, if you take ‘the shining spindle of the heavens’ to be the pole star, because the sky revolves around it—” As he paused for breath, the girl filled in for him, understanding what he meant. “Ah. Polaris isn’t above Ursa Minor at all, is it? It’s on its tail. And the Big Dipper isn’t the feet of Ursa Major either.”

“Exactly!” said Minato, delighted by the inordinate depth of her astronomical knowledge.

The girl grinned at the compliment, but almost immediately afterwards she lowered her head, bringing a finger to her lips in thought. “But this means that other parts of the song might have mistakes too,” she murmured to herself. “I’ll have to find out what they are.”

Minato’s heart gave a sudden lurch. “I just ruined the song for you, didn’t I?” he said, feeling cold.

“No, it’s all right. It was fun, like a pop quiz.” She beamed at him, putting his fears to rest. “And anyway,” she said, her hair waving softly with her movements, “I think it’s fine for it to be wrong.”

“Why’s that?” asked Minato.

“Because it doesn’t make the song any less wonderful,” she said. “You get to tell your friends, oh look, this part has a mistake! And then you get to all look over it together and have fun talking about it.” She nodded to herself, satisfied by her conclusion. “Yup, I think it is a good song after all.”

How casually she dismisses the matter! thought Minato with a renewed admiration. She was someone who had friends and was able to not get bogged down in minor details. Wouldn’t it be good if he could become like her, too?

One day, when he was finally discharged from hospital, once he had a group of good friends, he would play the clapping game with them—no, boys didn’t do that, did they?—he would tell them that he had met a girl. A girl that liked to look at the stars, who thought kindly of everything, whose expressions were so lively her face could never sit still, this strange, wonderful girl.

And as he imagined how all this might happen, he could almost seem to hear the ethereal, bell-like sounds of the stars ringing inside his heart.

“So,” Minato was telling Elnath, “she comes to visit her mother who’s been hospitalised. And normally she’s really cheerful, but when she was telling me this she looked so anxious that I felt like I really should do something to help her. I have magic, right? I should be able to help her mother get better or something.” His friend sat beside him and listened to this rare burst of loquacity without comment, his face betraying nothing of his feelings.

Day was breaking over the busy heart of the city. On the sides of every building dangled signs, every one of them lit and trying to outdo the other in a display of blinking ostentation, forming a contrast of sorts to the twinkling of the stars high up in the sky, these thronging boards with all their glue-on light bulbs and their plastic brilliances. The two had been flying through the sour, beer soused alleyways beneath the lights, but now, tiring of it, had stopped on top of a advertisement column for a brief rest. Elnath, as always jangling his bag of potential crystals absentmindedly, had been listening to Minato’s proposition. But in contrast to his friend’s excitement, Elnath wore an emotionless expression, although he kept his face downturned to hide it. Minato went on blithely: “Elnath, don’t you think you could use your power to help her mother get better?”

Elnath glanced briefly up at Minato before replying.

“Not possible.”

Minato started at Elnath’s tone. “But… we’ve got so many crystals already,” he said. “I can even do some magic now. Surely with what we have, we should be able to do something.”

“That’s not possible, I said,” Elnath repeated flatly.

“But―”

Elnath scowled. “Minato, there are things that I can do and would be happy to do, then there are things that I can do, but shouldn’t,” he said. “The potential crystals that we gather are supposed to be used to recover the spaceship’s engine fragments, and only that. Besides, I want to keep my involvement with the affairs of this world’s people at a minimum anyway. And also...”

“Also?” prompted Minato, tilting his head.

Elnath looked straight at Minato, his tone serious. “It’s better off if you don’t get too attached to this girl that comes to visit you,” he said.

The words came as such a surprise to Minato that he burst out in laughter.

“What, why?”

“I’m absolutely serious,” Elnath said.

“No, really but why?”

“It’s for your own good, Minato.”

Minato shrugged his shoulders dismissively. “She comes to visit whether or not I get attached to her, you know? What do you want me to do then?”

Elnath hmphed and looked briefly away. “Just act normal if she does. No reason not to enjoy yourself around her.”

Minato frowned, not understanding. What did he mean, enjoy yourself, but don’t get attached to her?

“You can’t expect me to stop caring about her,” pressed Minato again.

“I suppose I can’t,” answered Elnath.

“She’s the only thing I look forward to all day.”

“That she might be. But even so…”

“Then tell me why,” Minato said.

His friend glared at him. “This is exactly why,” he said fiercely. “Minato, can’t you see how hung up on her you are? How’re you going to take it when you stop being able to see her?”

Minato repeated blankly, “Stop being able to see her…?” Then he smacked a fist into his palm, understanding. “Ah. Once her mother gets better she won’t be coming to visit any more, so I should be preparing myself for that, right?”

Elnath shifted uneasily atop the column. “Well, yeah. Something along those lines.”

His eyes darted from place to place, and Minato had the distinct impression that he was being lied to about something.

Well, let him keep his secrets. “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it,” Minato said, defiantly looking upwards, away, at the sky. Though tonight, the lights of the city were too bright for the stars to be seen. “You never know. Maybe by the time her mother gets discharged from hospital, we’ll have gotten close enough for her to not mind giving me contact details or something. Or maybe she’ll be so happy at her mother getting discharged that she goes on to forget all about me. Both have the potential to happen, don’t they? But since she was able to see me when I was supposed to be invisible, and to find me all the way here in the hospital, I’d choose to believe that fate meant for us to meet.” He looked at Elnath’s eyes, hoping to see confirmation there.

But Elnath did not meet his eyes. Instead he turned to look down at the streets, at the drunks making their wavering progresses down the street, and said, each of his words dropping like a stone in the mud: “Your imagination’s better than I expected it to be.” And tightened his fist on the bag of potential crystals.

Minato sat on the bed, clutching his emptied bag of potential crystals in a hand. The crystals themselves hung suspended in the dark expanses of his room. What had Elnath wanted to say back then? he wondered. He looked at the girl beside him, her cheeks rosy with delight.

So she was going to go away, was she? And he was going to lose the one hope that he had in his life?

He tightened his grip on the bag.

Crystallised pieces of potential, he thought. Was there a crystal out there as well, formed from the potential they had of staying together? If there was, he would find it; and once he had it, never let it go.

The girl gave a sudden cry, her face lighting up: “The Winter Triangle!” She pointed ahead, where the Winter Triangle was indeed blazing merrily away. “See, I remembered!” She turned to Minato, who couldn’t help but smile back at her proud expression.

“It is easy to tell once you find Orion,” he said. “See that red star up on the top left? That’s the red supergiant Betelgeuse.”

The girl cocked her head as she regarded him. “I wonder, are supergiants really super gigantic?”

“Oh, absolutely,” Minato said. “They can have a diameter of up to a thousand times that of the sun.”

“A thousand!” she cried. Her eyes grew as round as saucers. She stared at Betelgeuse in wonder, exclaiming softly to herself. After a moment she said, “And what would it be like for Earth if that was our sun instead?”

“Swallowed up entirely,” answered Minato promptly. “The sun would reach all the way out to Jupiter’s orbit.”

“Um,” she said, her eyes widening just the slightest in unease.

“And what’s more,” added Minato, the words slipping out before he could stop them, “it’s reaching the end of its lifespan soon.”

He cursed himself as soon as he said it. To say something like that, just when they were having fun and everything was fine! It was all because Elnath had said what he had, about Minato and the girl not being able to see each other again.

She was looking uncertainly at him. “That star is going to explode soon,” he said. “When that happens, even Earth might be affected by it.”

“Oh,” the girl said softly, despondently.

“Ah, but it’s perfectly fine,” added Minato, hurriedly trying to make things right. “Betelgeuse is 600 light-years away, so it would take at least that much time for us to even detect its supernova. And by then science will have advanced far enough that we’d definitely be able to predict it and protect ourselves from it…”

But the girl was not listening. Her eyes never left the great, crimson star as she murmured to herself, “So there’ll be one less star in the sky…”

Minato caught his breath. What had distressed her wasn’t the imminent fate of the human race, but rather the simple fact that a small, albeit beautiful part of the night sky would be lost.

And he knew then she would certainly be just as sad as she was now, when the time came for them to part. And even after they had parted, as Elnath had feared they must, the girl would still carry all her memories of him within herself.

Just that knowledge was enough to warm his heart. He would go to live on in her memories, the boy who lived in a hospital room with stars more beautiful than at any planetarium, who claimed to have magic, who loved to talk about the stars…

“I just remembered!” cried the girl suddenly, startling Minato from his thoughts. “I made a star yesterday as well!”

“You… made one?” said Minato

“Yup.” The girl picked her bag up from the bed and began to rummage about it with her right hand, peering inside. “I folded it together with my mom. It’s a present for… oh.”

Her hand stopped.

The girl stared hard at the interior of the bag, eventually – reluctantly – bringing her hand out. Minato leaned in to see, having difficulty making out the object with the darkness all around.

What was sitting on her timidly extended palm was, as matter of fact, a thickly folded origami star. This star, however, was not entirely visible, for the two children were, after all, surrounded by the darkness of space.

“I thought you could use it as a decoration,” said the girl, a wobble in her voice, “but I guess you can’t see it well enough for that…”

She put all her heart into folding this, came the realisation to Minato. She wanted to thank me for showing space to her. She wanted to make me smile.

When he saw how the girl, with tears welling at her eyes, looked forlornly down at her hands, he almost began to feel tears pricking as well.

Minato made himself say, in as light a tone as he could manage, “Well, I like your star.”

The girl glowered at him. “Liar.”

“No, it’s true!” he protested. “See, this star is just like me.”

“Why’s that?” she demanded.

Because it’s small and faint and practically invisible, Minato thought. So small and so faint it might as well not be there. And even after all the effort and care that went into making it, it still ends up not being able to do a single thing except to sink slowly and sadly into the darkness.

He grinned back at her confused expression. Then he raised his right arm and summoned one of the potential crystals drifting around to him, a small crystal that gave off a wan, uncertain glow. This one, he remembered, he’d picked up in the hospital corridors last night. “I’ll give you this star in return,” he said.

The girl’s eyes darted from the pink crystal in Minato’s fingers to Minato’s eyes, and back again a few times before she managed to say, “Really?”

“I can always find more,” said Minato with a smile. “Besides, it looks like the star likes you.” The potential crystal twinkled up at her and made tinkling sounds like a baby’s hanging bells as if it was talking to her.

Could the crystals be used for any practical purpose, really, if you weren’t Elnath and didn’t have his knowledge and technology? Elnath himself had even said that the crystals would vanish soon after being expelled from a person, and because of that Minato had always assumed that the crystals were, generally, useless. But as a simple accessory it at least complemented the girl nicely with its light; and it would hopefully cheer her up a little, even if it might melt away at any moment, like a piece of sugar candy.

The two children exchanged their stars.

And then something happened as Minato’s fingers came into contact with the origami star. It was folded with ordinary paper, but somehow, as though his hand had suddenly become a high-powered sensor, the sensation of paper came across so strongly that he almost cried out. The sensation was neither one of hot nor cold, but rather something like an electric shock that ran through his hands as he took it, or maybe like the feeling of having a finger run over a fresh scar. It wasn’t so much unpleasant as it was simply surprising, but even so Minato was struck, a little bemused, by a fresh, renewed awareness of this was how it felt to hold something in his hand, that was now racing through his brain.

The girl, for her part, had been admiring the potential crystal with oohs and aahs. As she rolled it around her palm, the crystal cast its soft, pink glow over her features: over the tips of her hair, her eyes, over the lines of her lips and her cheek.

Minato closed his two hands softly around the origami star, watching her. If there was any power left at all in that potential crystal, he thought, then let it grant this girl’s mother the potential of recovering. Let it grant to this girl choices that led only to satisfying ends, and a life free of grief and sadness.

Grant to this girl, he willed, a future filled with endless hope and possibility.

It would be his gift. No matter that they never saw each other again, nor that she could never realise the full extent of what she was getting in this gift from him to her, which was no less than the very potential for happiness.

After all, he did have his magic, didn’t he? And she had made a wish to him. Well then, here was his answer, thought Minato, smiling a single, satisfied smile.